At Pixie, we are working on a Kubernetes native monitoring system which stores and processes the resulting data entirely within a user’s cluster. This is the first in a series of posts discussing techniques and best practices for effectively building Kubernetes native applications. In this post, we explore the trade-offs between using an air-gapped deployment that lives completely within a cluster and a system which splits the control and data planes between the cloud and cluster, respectively.

One benefit of building for the Kubernetes platform is that it simplifies the process of deploying applications to a user’s environment, often requiring only a few simple steps such as applying a set of YAMLs or installing a Helm Chart. Within minutes, users can easily have a running version of the application on their cluster. However, now that these applications are running entirely on prem, it becomes difficult for the developer to manage. In many cases, rolling out major updates or bug fixes relies on having the user manually update their deployment. This is unreliable for the developer and burdensome for the user.

Diagram of a connected on-prem architecture.

To address this problem, we propose a connected on-prem architecture which delegates the responsibility of managing the data and control planes of the application to the deployment running in the cluster and a developer-managed cloud environment, respectively. More concretely, the application deployed in the user’s cluster is solely responsible for collecting data and making that data accessible. Once the foundation of this data layer is established, the logic remains mostly stable and is infrequently updated. Meanwhile, a cloud-hosted system manages the core functionality and orchestration of the application. As the cloud is managed by the developer themselves, they are freely able to perform updates without any dependency on the users. This allows the developer to iterate quickly on the functionality of their system, all while maintaining data locality on prem.

This split-responsibility architecture is common in many hardware products, since external factors may make it challenging to deploy updates to software running on physical devices. For instance, despite these physical limitations, Ubiqiti’s UI is able to offer a rich feature-set by delegating functionality to their cloud and keeping their physical routers within the data plane. Similarly, WebRTC is a standard built into most modern browsers for handling voice and video data. Although browser updates are infrequent, having the separated data and control layers allows developers to freely build a diverse set of applications on top of WebRTC. This architecture is still relatively uncommon in enterprise software, but has been adopted by popular products such as Harness, Streamsets, and Anthos.

However, designing a connected on-prem architecture is easier said than done. When building such a system, one challenge you may encounter is how to query data from an application running on the user’s cluster via a UI hosted in the cloud. We explore two approaches for doing so:

- Making requests directly to the application in the cluster

- Proxying requests through the cloud

For brevity, we will refer to the application running on the user’s cluster as a satellite.

The simplest approach for executing the query on a satellite is to have the UI make the request directly to the satellite itself. To do this, the UI must be able to get the (1) status and (2) address of the satellite from the cloud, so that it knows whether the satellite is available for querying and where it should make requests to.

Diagram of Non-Passthrough Mode where the UI makes requests directly to the satellite agent itself.

A common technique to track the status of a program is to establish a heartbeat sequence between the program (the satellite) and the monitoring system (the cloud). This is typically done by having the satellite first send a registration message to the cloud. During registration, the satellite either provides an identifier or is assigned an identifier via the cloud, which is used to identify the satellite in subsequent heartbeat messages.

Following registration, the satellite begins sending periodic heartbeats to the cloud to indicate it is alive and healthy. Additional information can be sent in these heartbeats. In our case, we also attach the satellite’s IP address. Alternatively, the IP address could have been sent during registration, if it is not subject to change. The cloud records the satellite’s status and address so that it can be queried by the UI.

Now, when the UI wants to make a request to a satellite, it first queries the cloud for the address, then directly makes the request to that address.

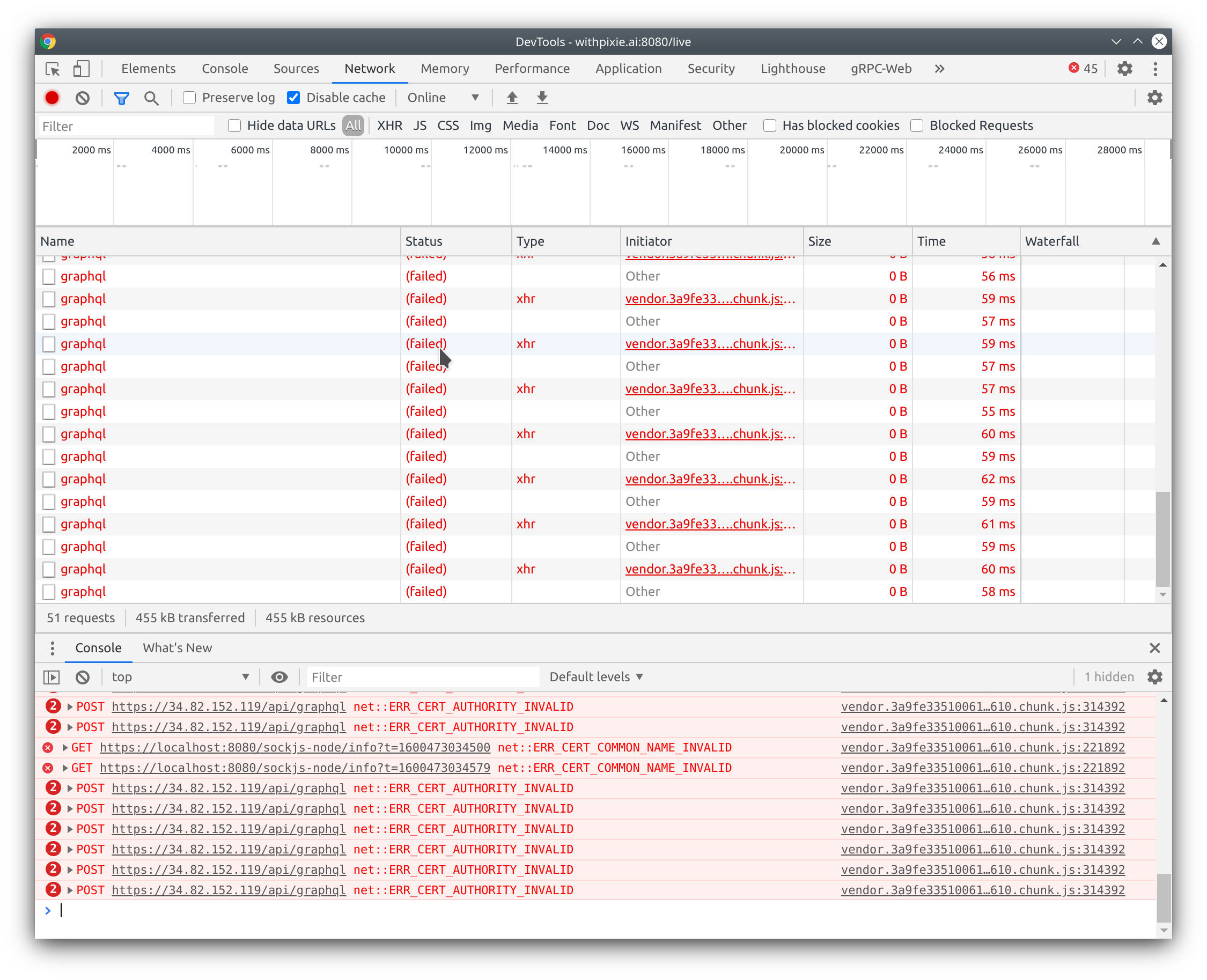

Great! That wasn’t too bad. In many cases, many cloud/distributed satellite architectures already communicate via heartbeats to track satellite state, so sending an additional address is no problem. However... If your UI is running on a browser and your satellite is responding over HTTPS (likely with self-signed certs), you are not done yet...

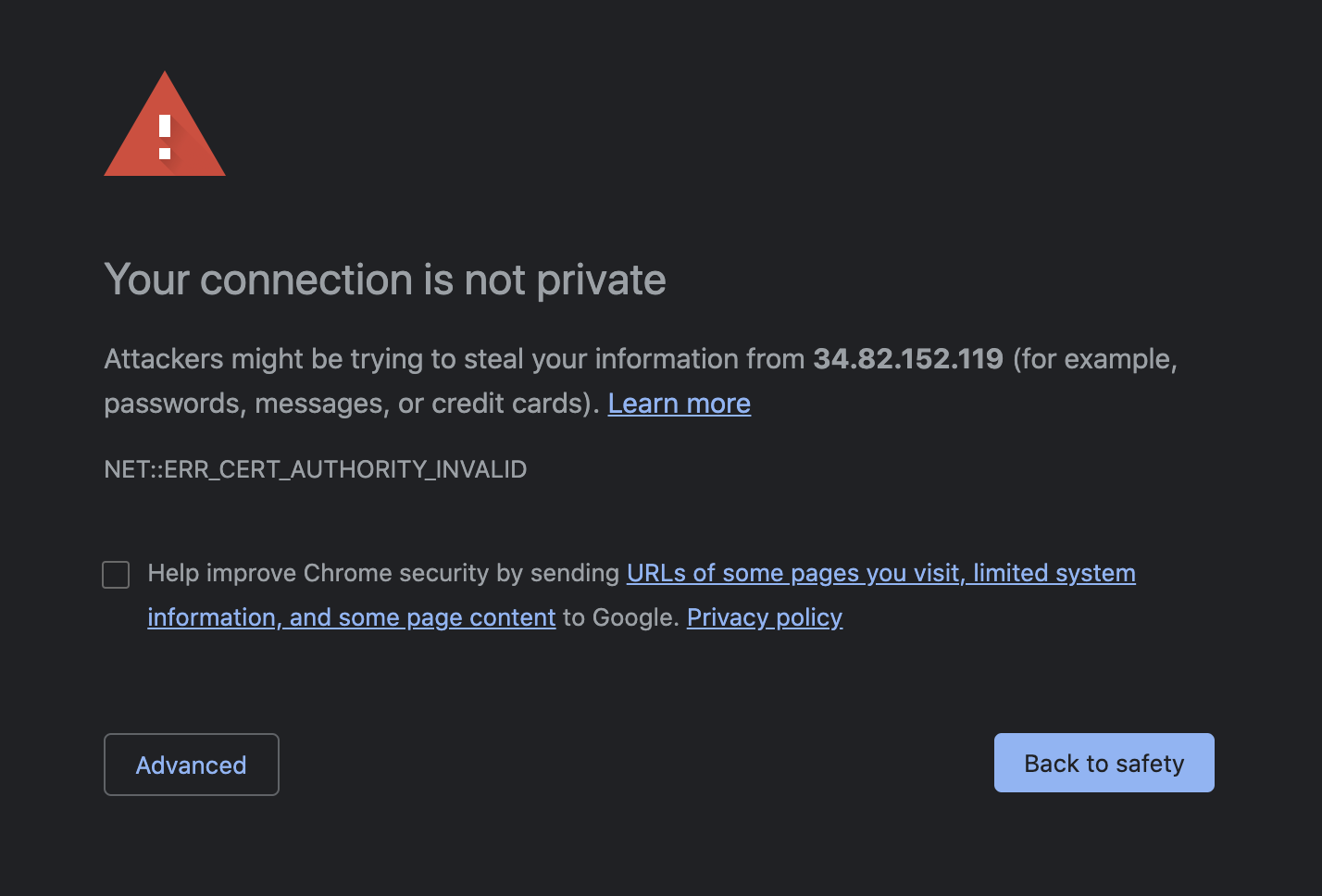

The browser is blocking our requests because of the satellite’s SSL certs! A user could go ahead and navigate directly to the satellite’s address, where the browser prompts the user with whether or not they want to bypass the invalid cert.

However, this would need to be done per satellite and is disruptive to the user’s overall experience. It is possible to generate SSL certs for IP addresses, but this is uncommon and isn’t available with most free Certificate Authorities. This approach is also complicated if the satellite’s IP address is subject to change.

Diagram of SSL certification flow for Non-Passthrough Mode.

To solve this problem, we used the following solution:

- Pre-generate SSL certs under a subdomain that you control, for instance:

<uuid>.satellites.yourdomain.com. This step is easy to do with any free Certificate Authority and can be safely done if the subdomain has a well-known DNS address. You should make sure to generate more SSL certs than the number of expected satellites. - When an satellite registers with the cloud, it should be assigned an unused SSL cert and associated subdomain. The SSL cert should be securely sent to the satellite and the satellite’s proxy should be updated to use the new cert.

- When the cloud receives the satellite’s IP address from its heartbeats, it updates the DNS record for the satellite’s subdomain to point to the IP address.

- When executing queries, the UI can now safely make requests to the satellite’s assigned subdomain rather than directly to its IP address, all with valid certs!

In the end, making requests directly to the satellites turned out to be more complicated (and hacky) than we’d originally thought. The solution also doesn’t scale well, since the SSL certs need to be pre-generated. Without having a fixed number of satellites, or an upperbound on the number of satellites, it isn’t long before all the certs have been assigned and someone needs to step in and manually generate more. It is possible to generate the certs and their DNS records on the fly, but we’ve found these operations can take too long to propagate to all networks. It is also important to note that this approach may violate the terms of service for automated SSL generation and is susceptible to usual security risks of wildcard certificates.

When a satellite is behind a firewall, it will only be queryable by users within the network. This further ensures that no sensitive data leaves the network.

Diagram of Passthrough Mode where UI requests are proxied through the cloud.

As seen in the previous approach, it is easiest to have the UI make requests to the cloud to avoid any certificate errors. However, we still want the actual query execution to be handled by the satellites themselves. To solve this, we architected another approach which follows these general steps:

- User initiates query via the UI.

- The cloud forwards the query to the appropriate satellite.

- Satellite send its responses back to the cloud.

- Cloud forwards responses back to the UI.

The cloud must be able to handle multiple queries to many different satellites at once. A satellite will stream batches of data in response, which the server needs to send to the correct requestor. With so many messages flying back and forth, all of which need to be contained within their own request/reply channels, we thought this would be the perfect job for a message bus.

The next question was: which message bus should we use?

We built up a list of criteria that we wanted our message bus to fulfill:

- It should receive and send messages quickly, especially since there is a user waiting at the receiving end.

- It should be able to handle relatively large messages. An satellite’s query response can be batched into many smaller messages, but the size of a single datapoint can still be non-trivial.

- Similarly, since an satellite’s response may be batched into many messages, the message bus should be able to handle a large influx of messages at any given time.

- It should be easy to start new channels at any time. We may want to create a new channel per request or per satellite, all of which we have no fixed number.

We briefly considered Google Pub/Sub, which had strict quota requirements (only 10,000 topics per Google project), and other projects such as Apache Pulsar. However, we primarily considered two messaging systems: Apache Kafka and NATS. General comparisons between Kafka and NATS have been discussed at length in other blogs. In this blog post, we aim to compare these two systems based on our requirements above.

We relied heavily on benchmarks that others have performed to judge latency based on message size and message volume. These results lean in favor of NATS.

We also wanted to test each system on our particular use-case, and performed the following benchmark to do so:

- Through a WebSocket run on the browser, send a message to the server.

- A service running on the server, called RequestProxyer, receives the message and puts it on topic A.

- A subscriber of topic A reads the message, and publishes it onto topic B.

- RequestProxyer reads the message on topic B, and writes a response back out to the WebSocket.

Diagram of the benchmark we used to test various message bus options.

In this case, the latency recorded for the benchmark is the time from which the websocket message is received in the RequestProxyer, to the time in which the server receives the response message from the subscriber.

These benchmarks were run on a 3-node GKE cluster with n1-standard-4 nodes, with a static 6-byte message. These results may not be generalizable to all environments. We also acknowledge that these systems were not built for this particular use-case.

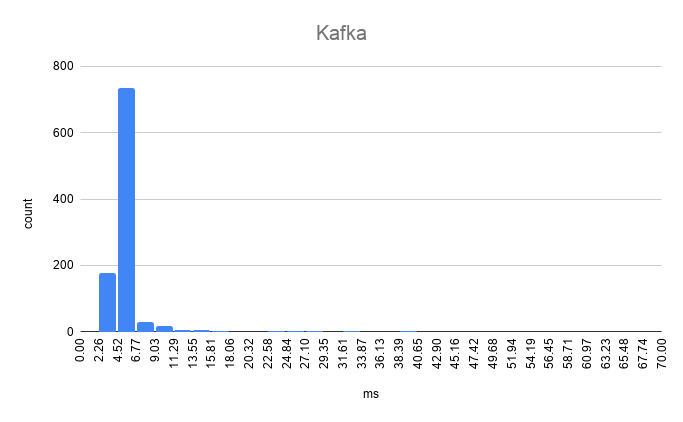

Self-Hosted Kafka

Kafka benchmark results

Avg.: 6.429768msp50: 4.882149msp95: 6.648898msp99: 55.596446msMax: 62.814922msMin: 3.586449ms

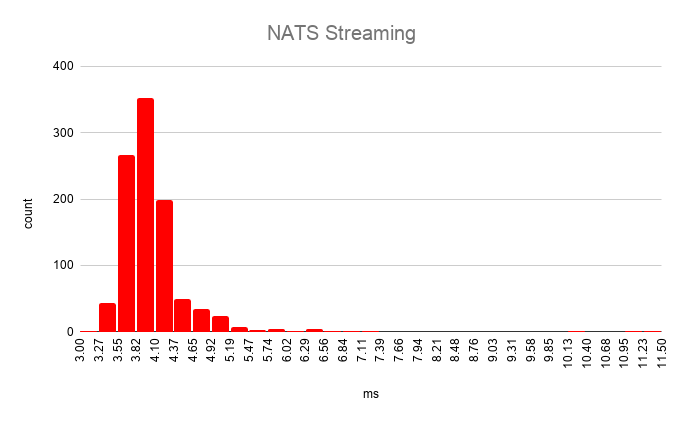

NATS Streaming

NATS Streaming benchmark results

Avg.: 4.059561msp50: 3.957979msp75: 4.185905msp95: 4.620923msp99: 6.349949msMax: 6.947179msMin: 3.449084ms

We ended up choosing NATS as our messaging system. Benchmarks performed by others and our own benchmark above showed that NATS is capable of efficiently handling our request and response messaging patterns. We also found it was extremely easy to create topics on-the-fly in NATS, whereas creating topics on Kafka can be fairly complicated since partitioning must be determined before start-up. Given that we will support many short-lived queries, we want to avoid any topic creation overhead. These points, paired with the lower operational complexity of NATS made it the clear winner for our case. It is important to note that Kafka's system is built to provide additional guarantees and has many positives, which may be necessary for other use cases.

Implementation for Passthrough Mode where UI requests are proxied through the cloud.

The actual implementation of our query request pipeline looks very similar to the benchmark case we ran above.

- The user initiates the query request through the UI.

- The cloud service responsible for handling the query requests receives the message and starts up a RequestProxyer instance in a new goroutine.

- The RequestProxyer generates an ID for the query and forwards the query and its ID to the correct satellite by putting a message on the

satellite/<satellite_id>NATS topic. It waits for the response on thereply-<query-IDNATS topic. - The service responsible for handling satellite communication (such as heartbeats) is subscribed to the

satellite/*NATS topic. It reads the query request and sends it to the appropriate satellite via its usual communication channels. The satellite streams the response back to this service. The service then puts these responses on thereply-<query-id>NATS topic. - The RequestProxyer receives the responses on the

reply-<query-id>topic and sends them back to the UI.

It is worth noting that in this approach, since data is now funneled through the cloud rather than directly from the satellite to the browser, there may be additional network latency.

In clusters behind a firewall, proxying the request through the cloud will allow data access to out-of-network users. This can be both a positive and negative, as it makes the application easier to use but relies on potentially sensitive data exiting the network.

We use both approaches in Pixie, and have found either method allows us to efficiently and reliably query data from our customer’s clusters. By providing both options, customers have the flexibility of choosing the architecture that best meets their security needs. We believe these techniques can be useful for any on-prem connected architecture, and the particular approach should be chosen depending on the overall use-case and constraints specific to the system itself.

Overall, designing an split data/control plane architecture for Kubernetes native applications will help developers iterate quickly despite the on-prem nature of Kubernetes deployments.

- Learn more about the Pixie Community Beta.

- Check out our open positions.

- Check out a recording of a talk on this blog post's content (video below):

Terms of Service|Privacy Policy

We are a Cloud Native Computing Foundation sandbox project.

Pixie was originally created and contributed by New Relic, Inc.

Copyright © 2018 - The Pixie Authors. All Rights Reserved. | Content distributed under CC BY 4.0.

The Linux Foundation has registered trademarks and uses trademarks. For a list of trademarks of The Linux Foundation, please see our Trademark Usage Page.

Pixie was originally created and contributed by New Relic, Inc.