etcd is a distributed key-value store designed to be a highly available and strongly consistent data store for distributed systems. In fact, by default Kubernetes itself uses etcd to store all of its cluster data, such as configs and metadata.

As with designing any system, different architectural decisions lead to different tradeoffs that impact the optimal way a system should be used and operated. In this blogpost, we discuss the inner workings of etcd to help draw conclusions for how you can best use this key-value store in your own application.

- The stability of etcd's Raft cluster is sensitive to network and disk IO. Add robust handling in clients (such as retries) for possible downtime, when the cluster has lost its leadership.

- Carefully tune the number of nodes in your cluster to account for failure tolerance and network utilization.

- If running a large datastore that can't fit into memory, try to run etcd with SSDs to help with reads and general disk latency.

- Range reads will be most efficient if you tend to write and read the same pieces of information together.

- Frequent compactions are essential to maintaining etcd's memory and disk usage.

- For applications with workloads where keys are frequently updated, defrags should be run to free up unneeded space to disk.

etcd is a key-value store built to serve data for highly distributed systems. Building an understanding of how etcd is designed to support this use-case can help reason through its best use. To do so, we will explore how etcd provides availability and consistency, and how it stores data internally. Design decisions, such as the consensus algorithm chosen for guaranteeing consistency, can heavily influence the system’s operation. Meanwhile, the underlying structure of the datastore can impact how the data is optimally accessed and managed. With these considerations in mind, etcd can serve as a reliable store for even the most critical data in your system.

In order to provide high availability, etcd is run as a cluster of replicated nodes. To ensure data consistency across these nodes, etcd uses a popular consensus algorithm called Raft. In Raft, one node is elected as leader, while the remaining nodes are designated as followers. The leader is responsible for maintaining the current state of the system and ensuring that the followers are up-to-date.

More specifically, the leader node has the following responsibilities: (1) maintaining leadership and (2) log replication.

The leader node must periodically send a heartbeat to all followers to notify them that it is still alive and active. If the followers have not received a heartbeat after a configurable timeout, a new leader election is initiated. During this process, the system will be unavailable, as a leader is necessary to enforce the current state.

By effect, the etcd cluster's stability is very sensitive to network and disk IO. This means that etcd's stability is susceptible to heavy workloads, both from itself and other applications running in the environment. It is recommended clients use robust handling, such as retries, to account for the possibility of lost leadership.

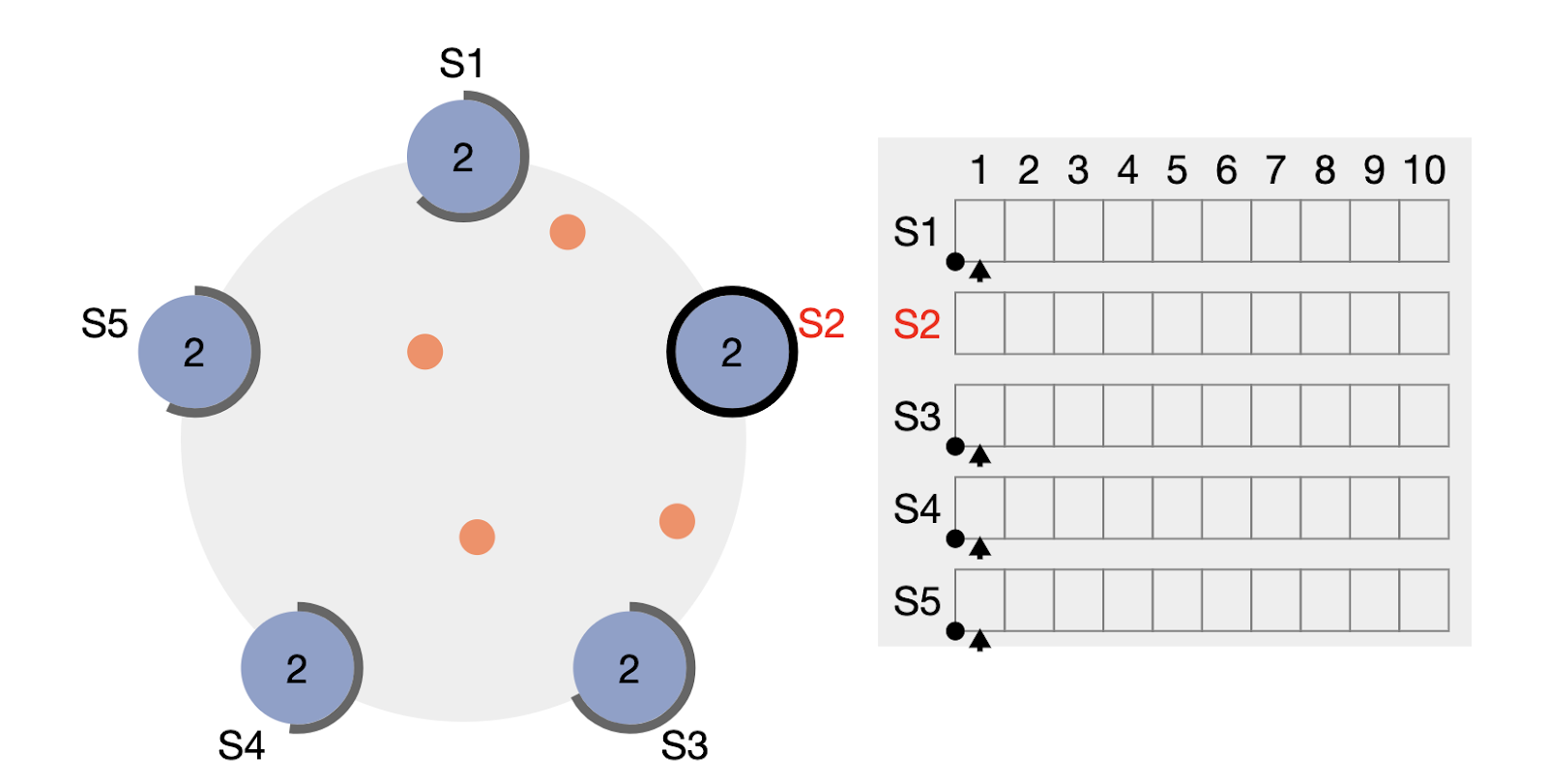

Screenshot from raft.github.io's helpful Raft Visualization, which demonstrates how Log Replication works. In this screenshot, S2 is the leader and broadcasting the log entries to all followers.

The leader node is responsible for handling incoming write transactions from the client. The write operation is written to a Raft log entry, which the leader broadcasts to the followers to ensure consistency across all nodes. Once a majority of the followers have successfully acknowledged and applied the Raft log entry, the leader considers the transaction as committed. If at any point the leader is unable to receive acknowledgement from the majority of followers, (for instance, if some node(s) fail), then the transaction cannot be committed and the write fails.

As a result, if the leader is unable to reach a majority, the cluster is declared to have "lost quorum" and no transactions can be made until it has recovered. This is why you should carefully tune the number of etcd nodes in your cluster to reduce the chance of lost quorum.

A good rule of thumb is to select an odd number of nodes. This is because adding an additional node to an odd number of nodes does not help increase the failure tolerance. Consider the following table, where the failure tolerance is the number of nodes that can fail without the cluster losing quorum:

| Cluster Size | Majority | Failure Tolerance |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 2 | 1 |

| 4 | 3 | 1 |

| 5 | 3 | 2 |

| 6 | 4 | 2 |

| 7 | 4 | 3 |

| 8 | 5 | 3 |

| 9 | 5 | 4 |

Table borrowed from https://etcd.io/docs/v3.4.0/faq/, showing that a cluster’s failure tolerance does not increase for a cluster of size N when compared to a cluster of size N-1, where N is even.

This helps visualize that a cluster of size 4 has the same failure tolerance as a cluster size of 3. Increasing the number of nodes will also result in an increase in network utilization, as the leader must send all log entries to every node. So, in the case of choosing an etcd cluster with 3 vs 4 nodes, 3 nodes will give you the same failure tolerance with less network utilization.

Now that we understand how etcd maintains high availability and consistency, let's discuss how data is actually stored in the system.

etcd's datastore is built on top of BoltDB, or more specifically, BBoltDB, a fork of BoltDB maintained by the etcd contributors.

Bolt is a Go key-value store which writes its data to a single memory-mapped file. This means that the underlying operating system is responsible for handling how the data is cached, typically caching as much of the file in memory as possible. Thus, Bolt shows high memory usage when working with large datasets. However, assuming that the relevant page is in the cache, this method allows for fast reads.

Bolt's underlying data structure is a B+ tree consisting of 4KB pages that are allocated as needed. The B+ tree structure helps with quick reads and sequential writes. However, Bolt does not perform as well on random writes, since the writes might be made to different pages on disk.

Bolt stores its data in a B+ tree, a structure that helps with quick reads and sequential writes. Highlighted in green is the path taken to find the data with 4 as the key.

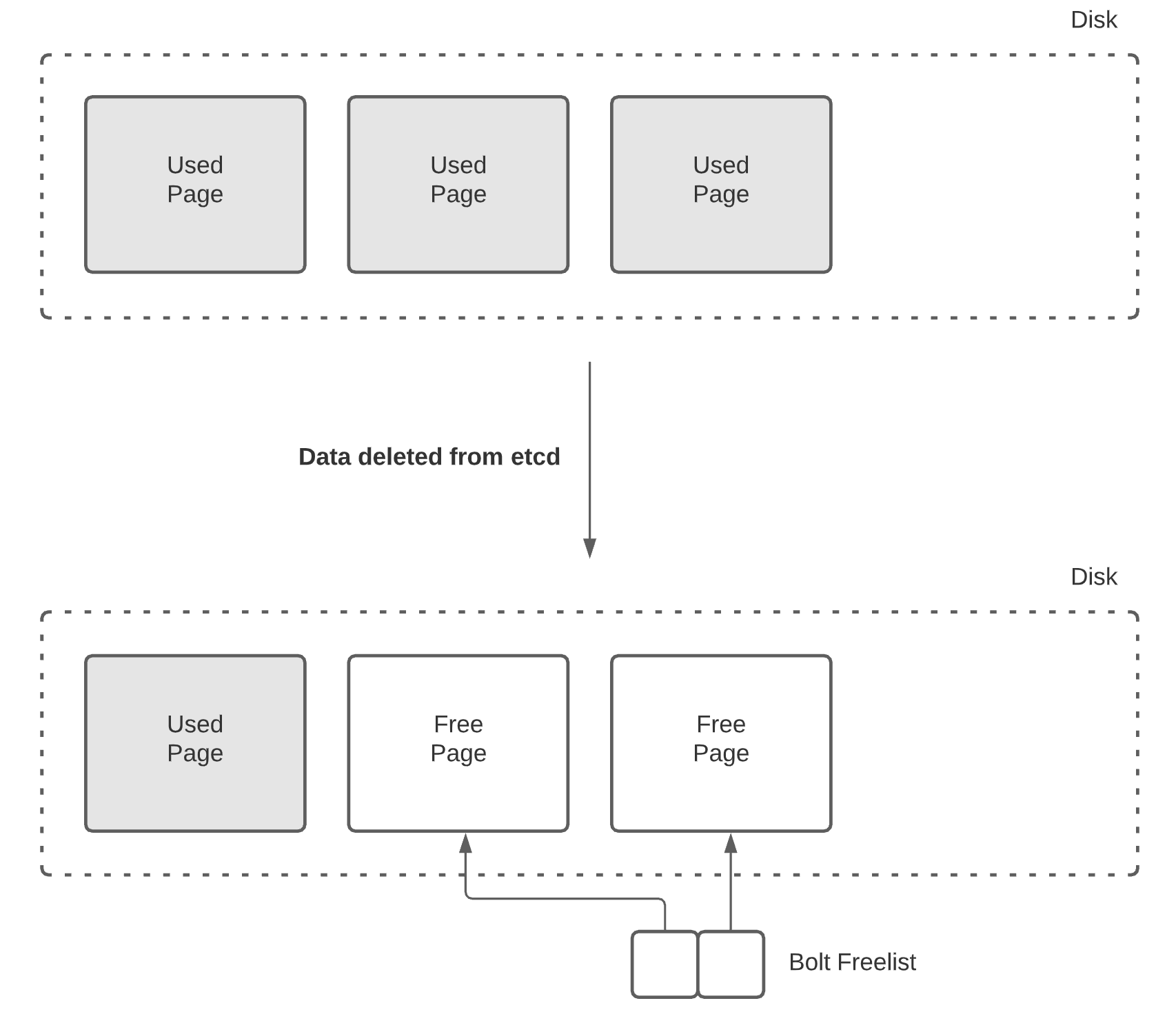

Bolt operations are copy-on-write. When a page is updated, it is copied to a completely new page. The old page is added to a "freelist", which Bolt refers to when it needs a new page. This means that deleting large amounts of data will not actually free up space on disk, as the pages are instead kept on Bolt's freelist for future use. In order to free up this space to disk, you will need to perform a defrag, which we'll discuss later in this post.

When data is deleted from Bolt, unused pages are not released back to disk, but kept in Bolt’s freelist for future use.

etcd uses MultiVersion Concurrency Control in order to safely handle concurrent operations. This goes hand-in-hand with the Raft protocol, as each version in MVCC corresponds to an index in the Raft log. To handle MVCC, etcd tracks changes by revisions. Each transaction made to etcd is a new revision. For example, if you were to load up a fresh instance of etcd and ran the following operations, the revision state would look like so:

---- Revision begins at 1 ----tx: [put foo bar] -> Revision is 2tx: [put foo1 bar1] -> Revision is 3tx: [put foo updatedBar] -> Revision is 4tx: [put foo2 bar2, put foo3 bar3] -> Revision is 5

By keeping a history of the revisions, etcd is able to provide the version history for specific keys. In the example above, you would just need to read Revisions 4 and 2 in order to see that the current value of foo is updatedBar, and the previous value was bar.

This means that keys must be associated with their revision numbers, along with their new values. To do so, etcd stores each operation in Bolt as the following key-value pairs:

key: (rev, sub, type)value: { key: keyName, value: keyValue, ...metadata }

Here, rev is the revision, sub is a number used to differentiate keys within a single revision (for example, multiple PUTs in a transaction), and type is an optional suffix, usually used for tombstoning.

For example, if you ran put foo hello following the above example, the corresponding Bolt entry might look like:

key: (6, 0, nil)value: { key: "foo", value: "hello", ...metadata }

By writing the keys in this scheme, etcd is able to make all writes sequential, circumventing Bolt's weakness to random writes.

However, this makes reading keys a little more difficult. For example, to find the current value of foo, you would have to read each entry starting from the latest revision, until finding the revision containing the value for foo.

To address the key reading problem described above, etcd builds an in-memory B-tree index which maps each key to its related revisions.

The actual keys and values of this tree are a little more complex, but the information it provides can most simply be reduced to:

A simplified example of etcd’s key index, which maps the keys to their revisions. Highlighted is the path taken to find 'foo3' in the tree.

This index says that foo was updated in revision 4, sub 0, and revision 2, sub 0. foo1 was updated in revision 3, sub 0, and so on. Using this information, you can easily find the current value of foo, along with its previous values, in Bolt.

etcd also supports range reads: "get me the values for foo1 to foo3" or "find me all keys and values prefixed with foo". Although these keys are logically sequential, they are not stored in Bolt as so. Performing the range read will require using the key index to find the keys that fall within the range, and then finding their associated revisions in Bolt. Given that these keys could have been written at any revision, these would essentially be random reads on Bolt. Efficiency for this operation heavily relies on the hope that most of Bolt's file is in the cache. If your datastore is large, chances are that the relevant pages will need to be read from disk. If you have a large dataset, run etcd with SSDs, as they are much faster than spinning disk.

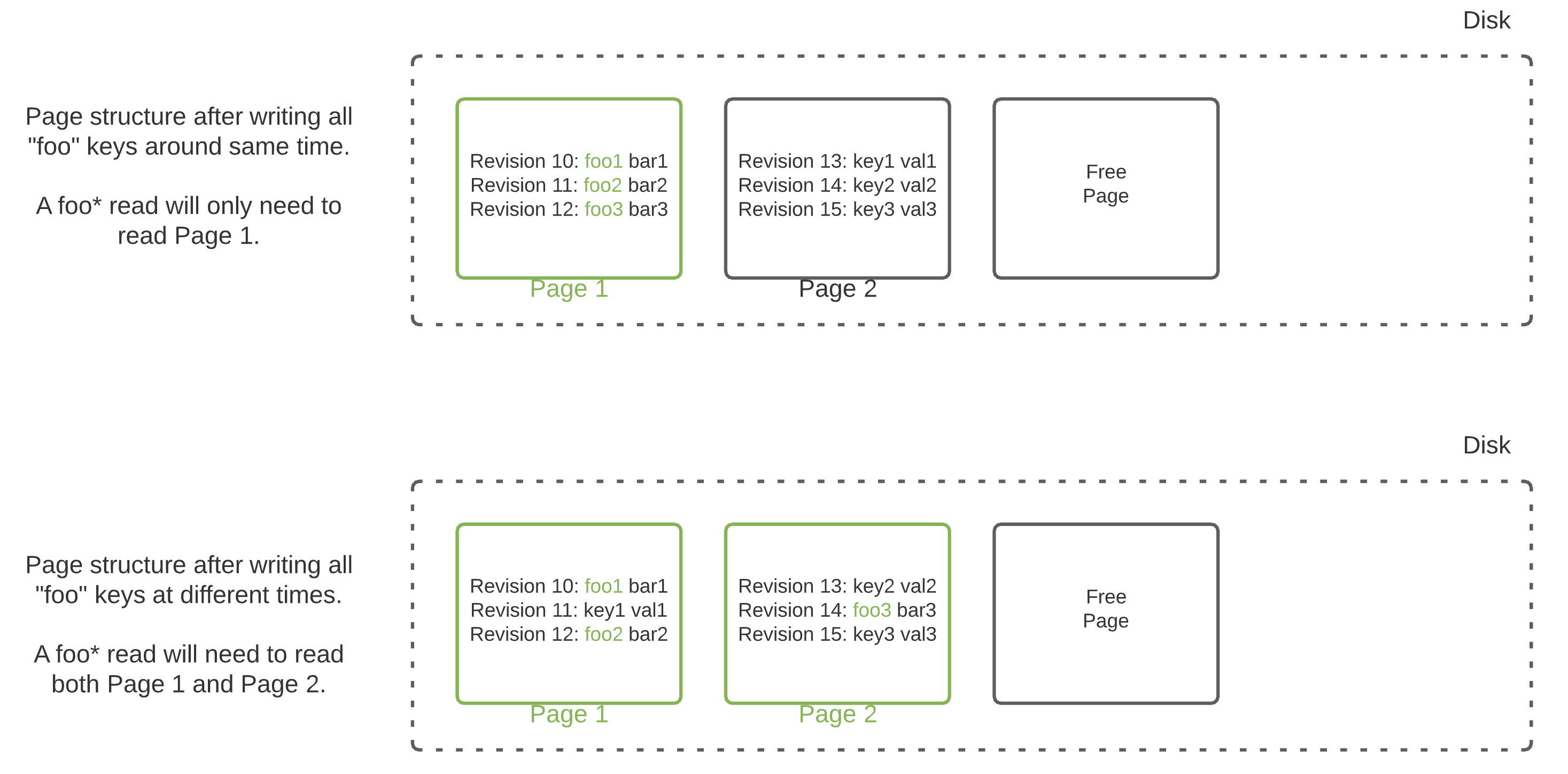

If anything, range reads will be slightly more efficient if you tend to read and write the same pieces of information together. For example, if you update all foo* keys at the same time (possibly in the same transaction), and later read all foo* keys, they will most likely be on the same page. This will help reduce the number of pages that may need to be read from disk.

An example of which pages are read on disk when trying to read all foo* keys, depending on the write pattern.

etcd's use of revisions and key history enables useful features, such as the watch capability, where you can listen for changes on a particular key or set of keys.

However, etcd's list of revisions can grow very large overtime, accumulating lots of disk and memory. Even if a large number of keys are deleted from etcd, the space will continue to grow since the prior history of those keys will still be retained. Frequent compactions are essential to maintaining etcd's memory and disk usage. A compaction in etcd will drop all superseded revisions smaller than the revision that is being compacted to.

For example, consider the following revision history:

Revision 2: foo1 bar1Revision 3: foo2 bar2Revision 4: foo3 bar3Revision 5: foo2 bar2_1Revision 6: foo3 bar3

If you were to compact to Revision 5, the saved history would be:

Revision 2: foo1 bar1Revision 5: foo2 bar2_1Revision 6: foo3 bar3

Here, revisions 3 and 4 were deleted, since their values were superseded by a later revision. Revision 2 is retained since there is no revision ≥ 5 with an updated value for foo1.

These compactions are just deletions in Bolt. As mentioned previously, Bolt does not release free pages back to disk, but hangs onto them in its freelist. In order to release the free pages back to disk, you must run a defrag in etcd. However, it is important to note that defrags will block any incoming reads and writes.

The frequency at which defrags should be run depend on your workload in etcd.

An example of what the pages on disk may look like after compaction, when mostly writing only new keys.

In general, if your workload on etcd mostly consists of creating new keys rather than updating existing keys, defrags won’t have a huge effect. This is because the number of revisions retained after a compaction would still be roughly equal to the number of total revisions ever created, thus requiring around the same number of pages.

An example of what the pages on disk may look like after compaction and defrag, when mostly updating existing keys.

However, if you have workloads where keys are frequently updated, defrags are necessary to free unused disk space. This is because a compaction will result in more deletes, as most of the key history can be pruned. In an extreme example, consider a case where your workload on etcd consists of updating only a single key. After many updates to the key, the total number of revisions will span N pages. After a compaction, this will be pruned to a single revision on one page, leaving N-1 pages free.

As with any system, the optimal use and operation of etcd is informed by tradeoffs based on the system’s architecture. To understand etcd’s best practices, we dove into the details for how etcd provides availability and consistency. This helped us draw conclusions about how applications should account for system failures, and how etcd should be deployed to best prevent these failures. Exploring the internals for how etcd stores its data allowed us to reason about useful access patterns and practices for managing memory. With these considerations in mind, etcd serves as a key component for storing metadata in our system at Pixie. We hope that this information also helps others determine how to best use etcd in their own applications.

- Learn more about Pixie.

- Check out our open positions.

Terms of Service|Privacy Policy

We are a Cloud Native Computing Foundation sandbox project.

Pixie was originally created and contributed by New Relic, Inc.

Copyright © 2018 - The Pixie Authors. All Rights Reserved. | Content distributed under CC BY 4.0.

The Linux Foundation has registered trademarks and uses trademarks. For a list of trademarks of The Linux Foundation, please see our Trademark Usage Page.

Pixie was originally created and contributed by New Relic, Inc.