eBPF technology has been a game-changer for applications that want to interact with the Linux kernel in a safe way. The use of eBPF probes has led to efficiency improvements and new capabilities in fields like observability, networking, and security.

One problem that hinders the wide-scale deployment of eBPF is the fact that it is challenging to build applications that are compatible across a wide range of Linux distributions.

If you’re fortunate enough to work in a uniform environment, this may not be such a big deal. But if you’re writing eBPF programs for general distribution, then you don’t get to control the environment. Your users will have a variety of Linux distributions, with different kernel versions, kernel configurations, and distribution-specific quirks.

Faced with such a problem, what can you do to make sure that your eBPF-based application will work on as many environments as possible?

In this blog post, we examine this question, and share some of our learnings from deploying Pixie across a wide range of environments.

Note: The problem of BPF portability is covered in detail by Andrii Nakryiko in his blog post on the subject. In this section, we rehash the problem briefly.

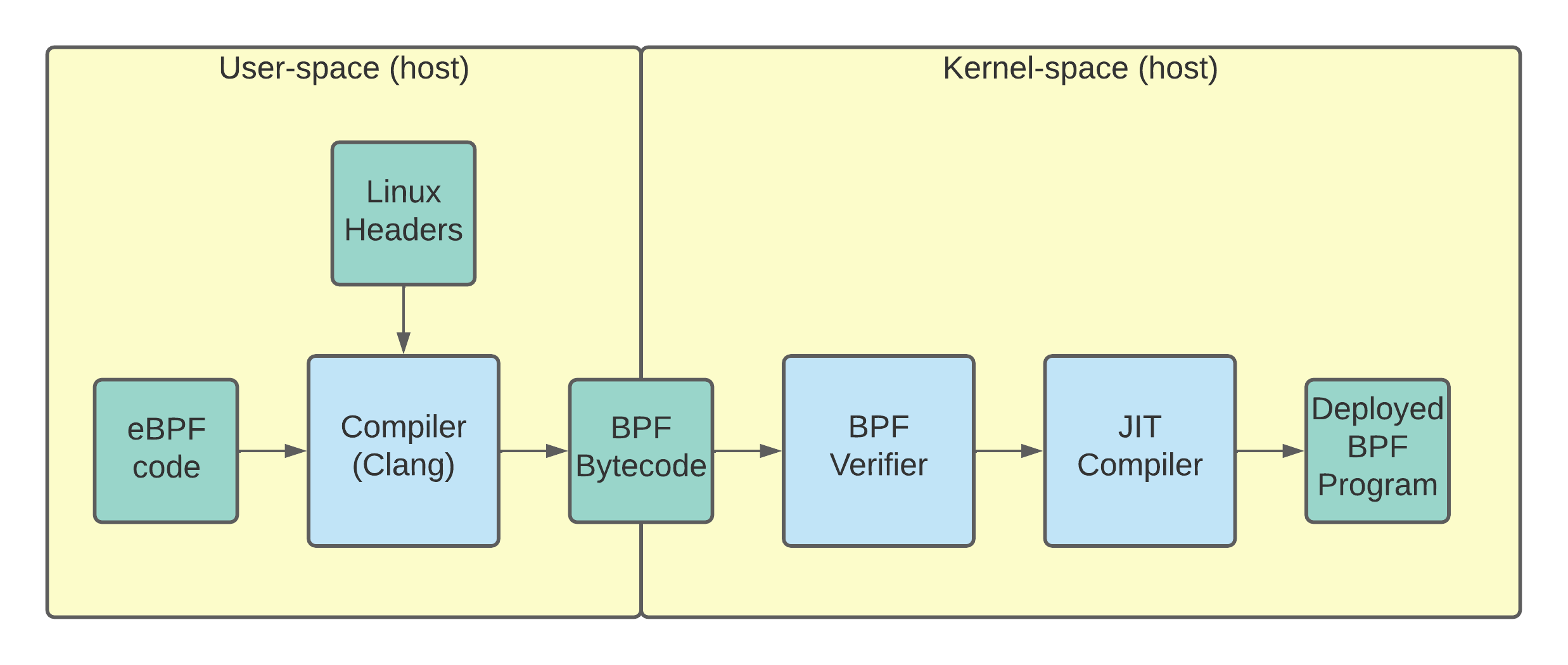

To understand why it can be problematic to deploy eBPF programs across different target environments, it’s important to first review the eBPF build pipeline. We’ll start with the basic flow used by frameworks like BCC. There are newer approaches with libbpf + CO-RE, but we’ll cover that later.

The BCC eBPF deployment flow: The eBPF code is compiled on the target host to make sure that the program is compatible.

In the basic flow, the eBPF code is compiled into BPF byte code, and then deployed into the kernel. Assuming that the BPF verifier doesn’t reject the code, the eBPF program is then run by the kernel whenever triggered by the appropriate event.

In this flow, it’s important to note that this entire process needs to happen on the host machine. One can’t simply compile to BPF bytecode on their local machine and then ship the bytecode to different host machines.

Why? Because each host may have a different kernel, and so kernel struct layouts may have changed.

Let’s make this more concrete with a couple of examples. First, let’s look at a very simple eBPF program that doesn’t have any portability issues:

// Map that stores counts of times triggered, by PID.BPF_HASH(counts_by_pid, uint32_t, int64_t);// Probe that counts every time it is triggered.// Can be used to count things like syscalls or particular functions.int syscall__probe_counter(struct pt_regs* ctx) {uint32_t tgid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;int64_t kInitVal = 0;int64_t* count = counts_by_pid.lookup_or_init(&tgid, &kInitVal);if (count != NULL) {*count = *count + 1;}return 0;}

The code above can be attached on a syscall (for example, the recv() syscall). Then, every time the syscall is made, the probe is triggered and the count for that PID is incremented. The counts are stored in a BPF map, which means the current counts for each PID can be read from user-space at any time to get the latest value.

This code is actually pretty robust to different kernel versions because it doesn’t rely on any kernel-specific structs. So if you manage to compile it with the wrong Linux headers, it will still work.

But now let’s tweak our example. Say we realize that process IDs (called TGIDs in the kernel) can be reused, and we don’t want to alias the counts. One thing we can do is to use the start_time of the process to differentiate recycled PIDs. So we might write the following code:

#include <linux/sched.h>struct tgid_ts_t {uint32_t tgid;uint64_t ts; // Timestamp when the process started.};// Effectively returns task->group_leader->real_start_time;// Note that before Linux 5.5, real_start_time was called start_boottime.static inline __attribute__((__always_inline__)) uint64_t get_tgid_start_time() {struct task_struct* task = (struct task_struct*)bpf_get_current_task();struct task_struct* group_leader_ptr = task->group_leader;uint64_t start_time = group_leader_ptr->start_time;return div_u64(start_time, NSEC_PER_SEC / USER_HZ);}// Map that stores counts of times triggered, by PID.BPF_HASH(counts_by_pid, struct tgid_ts_t, int64_t);// Probe that counts every time it is triggered.// Can be used to count things like syscalls or particular functions.int syscall__probe_counter(struct pt_regs* ctx) {uint32_t tgid = bpf_get_current_pid_tgid() >> 32;struct tgid_ts_t process_id = {};process_id.tgid = tgid;process_id.ts = get_tgid_start_time();int64_t kInitVal = 0;int64_t* count = counts_by_pid.lookup_or_init(&process_id, &kInitVal);if (count != NULL) {*count = *count + 1;}return 0;}

This code is similar to the original, but the counts map is now indexed by the PID plus the timestamp of when the process was started. To get the start time of a PID, however, we needed to read the internal kernel struct called the task_struct.

When the program above is compiled, it uses linux/sched.h to know where in the task_struct the group_leader and real_start_time fields are located. These offsets are hard-coded into the bytecode.

You can likely imagine why this would be brittle now. What if you compiled this with Linux 5.5 headers, but were able to deploy it on a host with Linux 5.8? Imagine what would happen if a new member was added to the struct task_struct:

struct task_struct {...struct task_struct *group_leader;...int cool_new_member;...uint64_t real_start_time;...}

If a new member is added to the struct, then the location of real_start_time in memory would change, and the compiled bytecode would look for real_start_time in the wrong location. If you somehow managed to deploy the compiled program on a machine with a different kernel version, you’d get wildly wrong results, because the eBPF program would read the wrong location in memory.

The picture gets one level more complicated with kernel configs. You may even think you have a perfect match in terms of Kernel versions, but if one kernel was built with a particular #define, it could also move the location of members, and you’d get unexpected results again.

In short, to make sure that your eBPF program produces the right results, it must be run on a machine with the same kernel as the machine it was compiled on.

The BCC solution to handling different struct layouts across kernel versions is to perform the compilation on the host, as shown in the initial figure. If you compile your BPF code on the target machine, then you’ll use the right headers, and life will be good.

There are two gotchas with this approach:

You must deploy a copy of the compiler (clang) with your eBPF code so that compilation can be performed on the target machine. This has both a space and time cost.

You are relying on the target machine having the Linux headers installed. If the Linux headers are missing, you won’t be able to compile your eBPF code.

We’re going to ignore problem #1 for the moment, since–though not efficient–the cost is only incurred when initially deploying eBPF programs. Problem #2, however, could prevent your application from deploying, and your users will be frustrated.

The BCC solution all comes down to having the Linux headers on the host. This way, you can compile and run your eBPF code on the same machine, avoiding any data structure mis-matches. This also means your target machines better have the Linux headers available.

The best case scenario is that the host system already has Linux headers installed. If you are running your eBPF application in a container, you’ll have to mount the headers into your container so your eBPF program can access it, but other than that life is good.

If the headers aren’t available, then we have to look for alternatives. If your users can be prodded to install the headers on the host by running something like sudo apt install linux-headers-$(uname -r), that should be your next option.

If it’s not practical to ask your users to install the headers, there’s still a few other approaches you can try. If the host kernel was built with CONFIG_IKHEADERS, then you can also find the headers at /sys/kernel/kheaders.tar.xz. Sometimes this is included as a kernel module that you’ll have to load. But once it’s there, you can essentially get the headers for building your eBPF code.

If none of the above works for you, then all hope is not lost, but you’re entering wary territory. It turns out you can try to use some headers from a “close” match, but this should only be used as a last result and with an understanding of the caveats. First you’ll have to modify the LINUX_VERSION_CODE (in a local copy of the headers) to match your kernel, otherwise the kernel will reject the eBPF code you compile (claiming a version mismatch). Second, you’ll still want to find the config flags used for your kernel and to apply them to the headers.

The above approach is a bit risky, but can work in practice if you’re not using structs that change much. For example, Pixie mostly works with public APIs like syscalls and the structs that drive them, so most fields that are accessed are very stable across versions. If, on the other hand, you actually try to access the linux task_struct, then your risk would be much higher, and this is not a recommended strategy.

Given that it is risky to use mismatched headers if you’re poking at Linux structs, what else can you do? Ultimately, you’ll want to move to libbpf + CO-RE (discussed in the next section), but there are other tricks you can sometimes use. For example, Pixie does actually access the TGID real_start_time from the task_struct, but to avoid reading the wrong value we take a dynamic approach for locating these members that might move.

Instead of relying on the Linux headers, we actually use a test probe to find the offsets of certain struct fields dynamically. Specifically, to find the location of the real_start_time within task_struct, we fork() a process and then probe it. We know the expected real_start_time of the process from /proc/<pid>/stat so then we just have to find the same value in memory in the probe. Once we find it, we have dynamically figured out where the information is located, and we are robust to different kernel versions.

You can see an example of this approach in the Pixie code base here.

This approach won’t work for all the fields that you may be interested in, but if you have some degree of control over the population of the struct, you can use these sorts of tricks to make your eBPF more robust.

Admittedly, these tricks will only get you so far. The better solution is to move to libbpf and CO-RE.

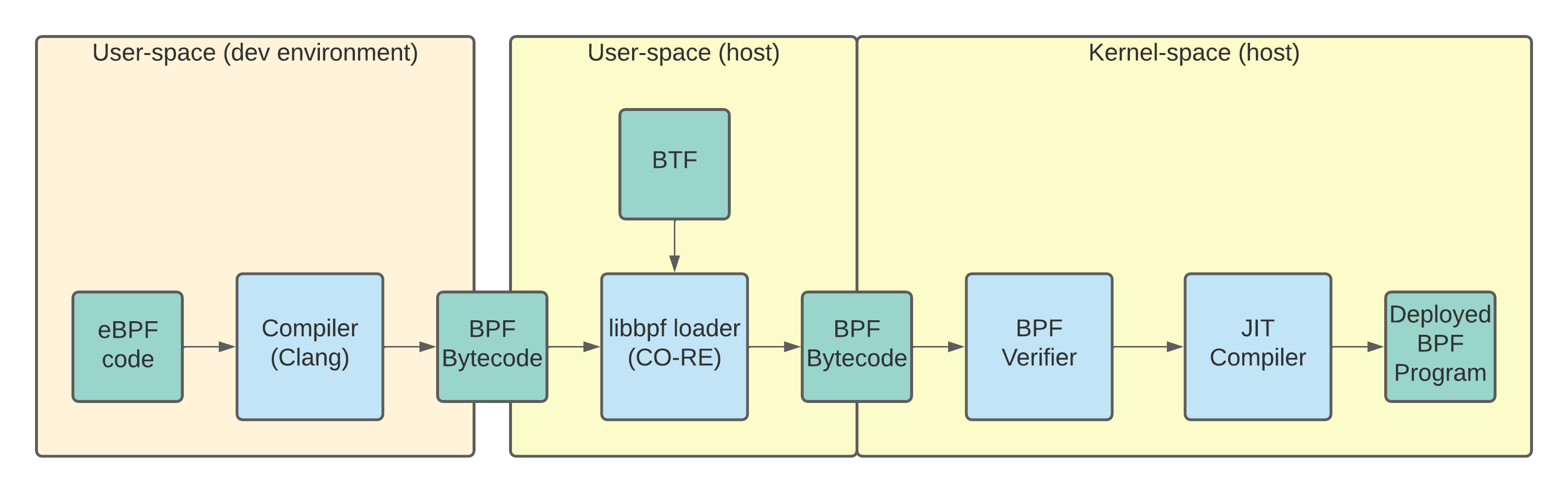

To resolve the problems with (1) requiring host Linux headers and (2) the cost of including LLVM/Clang with eBPF code, the eBPF community has developed libbpf + CO-RE.

The key to CO-RE is something called BTF (BPF Type Format) which encodes the struct offsets of kernel structs for a given kernel version.

The information in BTF enables the BPF program loader to make adjustments to your pre-compiled eBPF code so that it looks for the desired information at the right offsets in memory.

Once again, Andrii Nakryiko's blog post has more details on this topic.

With CO-RE, instead of requiring Linux headers on the target machine, you need the BTF information.

The libbpf + CO-RE compilation flow: The eBPF code is pre-compiled on your local dev machine. BTF information is used to modify the compiled bytecode for the host kernel.

In terms of compile-time resources (time and space), CO-RE is a huge win. But what about portability? One could argue that in either case, we need information about the host. In one case we need headers, while in the other we need the kernel’s BTF.

So how do you get the BTF for your host machine? If your kernel was compiled with CONFIG_DEBUG_INFO_BTF=y, you’re in luck. But if there’s no BTF, have we just replaced one problem with another?

For example, for Pixie, we support kernels as old as 4.14, which won’t have BTF built-in; to make sure we have the widest possible support across kernel versions, we have found ourselves in a spot where we have had to stick with BCC. What else can one do?

Fortunately, there are cool new projects on the horizon. Check out Part 2 to see how to use CO-RE with a BTF repository called BTFHub to enable deployments across a wide range of machines.

Terms of Service|Privacy Policy

We are a Cloud Native Computing Foundation sandbox project.

Pixie was originally created and contributed by New Relic, Inc.

Copyright © 2018 - The Pixie Authors. All Rights Reserved. | Content distributed under CC BY 4.0.

The Linux Foundation has registered trademarks and uses trademarks. For a list of trademarks of The Linux Foundation, please see our Trademark Usage Page.

Pixie was originally created and contributed by New Relic, Inc.